Harold Koda in a grey suit. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art/BFAnyc.com/Joe Schildhorn

Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Harold Koda reveals a love for gray suits and a drive pushed (with great success) by procrastination.

When did you realize you wanted to be a fashion scholar?

Koda: You know I don't think I ever really wanted to be a fashion scholar. (laughs) I did realize I wanted to do something in fashion.

In the 1970s, when I was in graduate school studying art history, I would look at Interview magazine and see pictures of Andy Warhol and Truman Capote hanging out with Halston and Bianca Jagger, and I thought, there's this real intersection of art and fashion and celebrity that's happening. It seemed fun, rather than serious. So I thought, maybe there is a way to intersect the two.

My first job was as an intern in the Costume Institute working for the restorer at the time, Elizabeth Lawrence, who was lovely. The whole world was very, very different in costume and textiles. It's not that long ago, but it's really ancient history, when you had almost 70 volunteer women who would come in on different days of the week, about 10 or more a day, to work on the shows and on the dresses in the collection.

Now, we don't let anyone handle the material unless they are a conservator and have professional training. But back then, 40 years ago, it was a very different place, and the best thing for somebody like me, because I'm reasonably good with my hands.

One of the first things I dressed was an 1880s mourning dress in black satin and there were these wrinkles in the bodice, horizontal lines. The curator at the time came in said, 'Oh, the way you can get rid of those is to steam them with your fingers.' (laughs) Now this is something that today would make a conservator chop my hands off, steam it with your fingers!

Later I took classes at FIT and realized how silly it was, what I had been told. In fact, what I should have done was just lower the waist line. Then the wrinkles would drop.

French Silk Mourning Dress, circa 1880. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Gift of Mrs. R. Thornton Wilson, 1943

So it's just totally different now.

Koda: Yes, all of it! So here was someone who had no real exposure to historic dress just dropped into the middle of it and getting the opportunity to work with one of the world's most extraordinary collections of costume.

For me it was a kind of oasis. You had all of these (laughs)-this sounds sort of weird-but there were all of these very, very privileged, very social women. The women who were doing this were wives with mogul husbands. This was something they did.

There was this one woman, for instance, who you knew didn't even know where the kitchen was in her 14-room apartment. But what she was really brilliant at doing-she could iron. So here you had this person who you know has hot and cold running help ironing an 1890s petticoat like the best lady's maid in history.

For me it was like a social register sewing bee. I'd be working on my project and they'd be talking about things. As a 23-year-old, it all seemed so jaded and sophisticated and weird.

Charles James Ball Gowns, 1948. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photograph by Cecil Beaton. Copyright Condé Nast.

Who or what has influenced your work?

Koda: It's actually two people. Diana Vreeland introduced to me the idea that clothing can carry all kinds of narratives, but you have to make it explicit to the public. You have to sell the object-you can't just say I'm going to put this dress up and have it stand there and people will come, you have to make it interesting enough for them to come. If you have something to teach people, they have to want to learn it. That is what I got from Mrs. Vreeland: You need to introduce showmanship if you are serious about communicating ideas

Then there was Richard Martin who was my boss for almost 20 years. He wasn't about the nitty-gritty of clothes, he didn't know how anything was made. For him it was more the meta notion of what a dress was about. I used to tease him. I'd say, 'You know you're like a French theorist-all cobwebs in the sky.'

But in fact he elevated the notion of studying clothing beyond simply, 'In 1880, women in Paris wore this.' He introduced notions of other concepts to clothes. We did one show that was about flowers and patterns, and he even made that an intellectual investigation.

So those two people-Richard for introducing me to the idea that taking the conceptual approach to the interpretation of dress is worthy, and Mrs. Vreeland, for introducing me to the idea that clothing is something that can carry incredibly compelling stories.

Do you feel that your aesthetic choices have changed since you began your career?

Koda: I'm basically a minimalist Modernist, but I really love it when other people are maximalist Baroque. When it is not about myself, I like the whole spectrum of design and aesthetics.

What are you currently working on?

Koda: We're working on the Charles James exhibition, right in the middle of finishing up the photography for the catalogue, and it's going to be a revelation to people. James was someone who forged his own way. His dresses might look like 'New Look' dresses, but the way he's made them is completely individual. He's a stand-alone couturier.

Harold Koda (left) with Anna Wintour (center) and Giorgio Armani (right). Photo: Venturelli/WireImage

Is there something specific that he does absolutely different than everyone else?

Koda: What he does is take an idea or technique from the past and completely transform it in his application. For somebody who likes construction and technique, it's really been incredible to study his work.

And that's what we are going to do with the exhibition. We want the general public to understand how he did it-demonstrate not just simply beautiful dresses but, for the first time, how someone makes a dress in a personal and distinctive way.

What's inspiring you at the moment?

Koda: I'm really not a theater person-I always say I don't have the theater gene-but recently I saw Matthew Bourne's Sleeping Beauty. He introduces vampires to the story. It sounds like it might not work, but it just really did for me. When I see a classic transformed into something very original, that inspires me. Because I think that's sort of my job-to take historic dress and present it to a contemporary audience in a way that makes it relevant to them.

If you present history as history, it might be too much removed. My challenge is taking something distant and making it relevant, like Sleeping Beauty, where you have all the essential parts of a story and then completely flip them to make it equally compelling and memorable. It was fun. I left that production on a high.

What helps you feel creative?

Koda: I've always been a procrastinator-I just leave things to the bitter, bitter end-so really, it is anxiety. I get so anxious.

For other people, anxiety makes them freeze: Anxiety just makes me finally do something-that's what really makes me creative. I know it's not a fun thing, it's not like I go off into a Zen garden, but that's really what it is.

That's interesting-and actually probably quite realistic for a lot of people.

Koda: When I was in college and I had a therapist, I said, 'I don't know why I do this. I don't study until the very last minute, and it's really horrible. But I keep doing it, and I just keep procrastinating.'

And he says, 'Well how do you do?'

And I say, 'Well I do OK.'

And he says, 'Well what's feeding it is you do OK. If you didn't do OK, you would stop doing it.'

The system works.

Koda: Yeah. But it's bad, It's not a good system. But it works. It does work. There can be different systems for different people.

Are there any widely accepted rules that you love to throw out the window?

Koda: No, I am so conservative. I really follow the rules, which is why I think I admire creative people so much. Creative people are always testing the limits and always pushing us beyond any kind of expectation. I always follow the rules, but I do try to insert in my conservatism a kind of sense of novelty. So I like to work within the rules but within a framework that appears to be an innovation or a new way of looking at it. You're working within the system, but somehow looking at it in a different way.

I'm really not a rule breaker.

What are some fashion designers that have always visually inspired you, and continue to stand out for you today?

Koda: Madeleine Vionnet who worked in the teens, 20s, and 30s and was the great proponent of the bias. She just took fabric and turned it at a diagonal, and that introduces a lot of flexibility. So with these really original cuts she was able to create fashion that drifted over the body, shaped its self over the body.

The other designer that I find really extraordinary is Cristóbal Balenciaga. Unlike Vionnet, who was introducing something completely new, he looked to the past, and just kept paring it down, paring it down, revisiting it, but always working with his materials until he came to the really pure reductive level of design, where it was very, very lightly done, but retained this sculptural presence.

In terms of contemporary designers, because I love technique so much, I have to say it is Azzedine Alaia, who actually has qualities of both Vionnet and Balenciaga.

What qualities do you like to have present in your own wardrobe?

Koda: Brainlessness. (laughs) I go to my closet, and I have only gray suits-well actually I have a navy blazer and sports coats for the country-but really most of the time, it's just a uniform. I like what Francine du Plessix Gray said about her stepfather, I am going to just paraphrase, but it was something to the effect that he dressed with an almost monastic austerity-that's what I aspire to, a repetitive, monastic austerity.

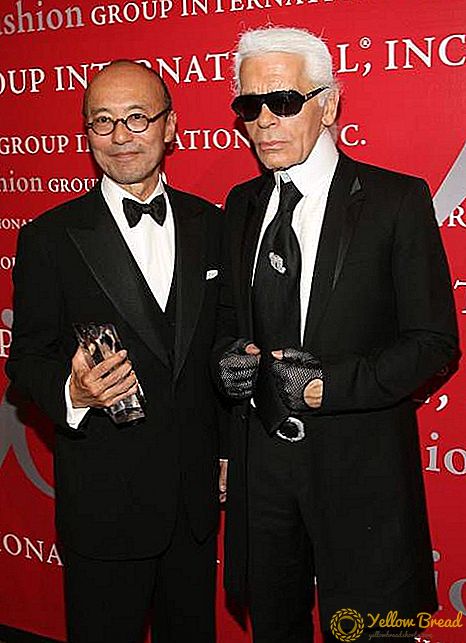

Getty ImagesStephen Lovekin/Getty Images

Harold Koda (left) with designer Karl Lagerfeld (right). Photo: Stephen Lovekin/Getty Images

What has been one of your favorite projects over the years?

Koda: There are two. Both of these have to do with working with living designers. One was the Chanel show where we got to work with Karl Lagerfeld. Spending a half an hour with him is so invigorating because you see a true polymath, somebody who knows something about everything and expresses it without a filter-it's so exciting.

The other was working with Miuccia Prada who is again an intelligence that whatever you think, she thinks about the same thing from a completely different direction. When you are dealing with creative talent like that, it makes the whole project. It doesn't mean that it's easy, because they are also very, very opinionated about things, but in the challenge, there is this thrill of being able to partner with a great mind.

It's not just about a good eye, these are two people who have great minds.

What do you do to in your downtime?

Koda: I spend much too much time on real estate site and auction site 1stdibs. I am addicted to looking at real estate. Everywhere I go I think about having a house, and apartment, or in one instance a monastery there. We are building an addition to our house in the country and right now I'm focused on something called Swedish Grace which was a design period in Sweden between the wars. In the 1920s they had a return to classicism and I love the designs of that movement. I am constantly going through 1stdibs, and Bukowski's, an auction house in Stockholm.

Basically, I spend much too much time on the web looking at furniture and dreaming about property.

Have you traveled somewhere recently to a place that influenced you?

Koda: I love Miami, I just love Miami. There's something exciting, and up-and-coming and no rules-and because I am just so uptight, it is completely counter to my personality, and I just love that.

Recently, we went on a trip to Sintra, Portugal where the summer palaces of the Lisbon aristocracy surround the King's retreat. There's a very wet, high mountain that looks out over the Atlantic ocean and it is absolutely poetic. We stayed in an 18th-century palace. We went in the late spring, and it was all misty, with rain. It's a romantic, very wet spot, everything is covered in moss.

While we were in this palace, they were filming an early 19th century movie, so every morning we would wake up to rain-it was actually misty and not raining-because the movie crew would set up these rain machines outside our window. And then we'd hear horses and a carriage coming down the gravel. They kept doing this scene over and over again, so you felt like you were in a palace in the 18th century with horsemen and carriages coming up to your door in the rain. Then of course by the afternoon, they'd broken it all away. Every morning for three days we heard that.

But what inspired me about the trip was this one very strange villa built by an eccentric millionaire at the turn of the century. He was into mysticism. In his garden is this well. You can walk down into this well, almost 100 feet down a narrow, wet, spirling, stone staircase, and at the bottom there is a mystical Masonic sign in the floor. Then you have two exits. You can see faint light in one of them, and the other exit is absolutely dark.

So what you do is choose one or the other to get out of this place. The thing that I love about it is, it is so counterintuitive. If you let your mind work, you choose the light, but that leads you into a waterfall and you have to walk over these wet stones, it's really complicated.

But if you go with your emotion and go into the darkness, it leads you straight out. That really inspired me. Don't just fall back on what is logical, which is the bright path. Sometimes do what is dangerous and mysterious, and it might lead you to a more efficient conclusion.